Chapter 1: The Mathematics of Learning Guarantees

1.1 Introduction to Learning Theory

When a machine learning algorithm examines data and produces a model, how can we be confident that this model will perform well on new, unseen examples? This fundamental question lies at the heart of learning theory. Rather than focusing on specific algorithms like neural networks or decision trees, learning theory provides a mathematical framework to understand when and why learning works.

Consider a simple problem: we want to determine if an email is spam based on its content. We might train a classifier on thousands of labeled examples, but how do we know if it will work well on future emails? Intuitively, we expect that with enough diverse training examples, our classifier should generalize well to new data. But how many examples are “enough”? And how can we formally prove this intuition?

Learning theory gives us tools to answer these questions with mathematical precision. Instead of vague assurances, we can derive exact bounds on how likely our algorithm is to succeed and how much data it needs. This chapter introduces the fundamental concepts needed to build such guarantees.

1.2 Key Notation and Definitions

To reason precisely about learning, we need formal definitions. Let’s establish our notation:

- Input space \(\mathcal{X}\): The set of all possible inputs (e.g., all possible emails)

- Output space \(\mathcal{Y}\): The set of all possible outputs (e.g., “spam” or “not spam”)

- Training sample \(S = ((x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2), ..., (x_m, y_m))\): A set of m labeled examples

- \(S|_x = (x_1, x_2, ..., x_m)\): Just the inputs from the training sample

- Distribution \(\mathcal{D}\): The probability distribution from which examples are drawn

- Labeling function \(f: \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}\): The true, underlying function we’re trying to learn

- Hypothesis class \(\mathcal{H}\): The set of possible prediction rules our algorithm can output

- Hypothesis \(h \in \mathcal{H}\): A specific prediction rule (e.g., a specific classifier)

Given these definitions, we can formalize two crucial concepts:

True error: The probability that a hypothesis makes an incorrect prediction on an example drawn from the true distribution: \[L_{(D,f)}(h) = \mathbb{P}_{x \sim D}[h(x) \neq f(x)]\]

Training error: The fraction of mistakes a hypothesis makes on the training sample: \[L_S(h) = \frac{1}{m}\sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathbb{1}_{[h(x_i) \neq y_i]}\] where \(\mathbb{1}\) is the indicator function that equals 1 when \(h(x_i) \neq y_i\) and 0 otherwise.

Our learning algorithm examines the training data \(S\) and outputs a hypothesis \(h_S\). We want \(h_S\) to have low true error, but we can only measure its training error. The key challenge in learning theory is understanding the relationship between these two errors.

For simplicity, we’ll initially work under the realizability assumption: there exists at least one hypothesis \(h^* \in \mathcal{H}\) with zero true error (\(L_{(D,f)}(h^*) = 0\)). This means our hypothesis class contains at least one perfect predictor.

1.3 Understanding Failure Events

When does a learning algorithm fail? We define failure as producing a hypothesis with true error exceeding some acceptable threshold \(\epsilon\):

\[L_{(D,f)}(h_S) > \epsilon\]

Our goal is to understand how likely this failure is when we train on \(m\) randomly drawn examples.

To approach this systematically, let’s define the set of “bad” hypotheses:

\[\mathcal{H}_B = \{h \in \mathcal{H} : L_{(D,f)}(h) > \epsilon\}\]

These are hypotheses that perform poorly on the true distribution. If our algorithm outputs such a hypothesis, it fails.

But here’s the key insight: under the realizability assumption, our algorithm will always output a hypothesis with zero training error. So failure can only happen if some “bad” hypothesis also happens to have zero training error on our sample.

This leads us to define the set of “misleading samples”:

\[M = \{S|_x : \exists h \in \mathcal{H}_B, L_S(h) = 0\}\]

These are training sets where at least one bad hypothesis looks perfect (has zero training error). Since our algorithm chooses a hypothesis with zero training error, if a bad hypothesis has zero training error, our algorithm might select it and fail.

The crucial relationship is: \[\{S|_x : L_{(D,f)}(h_S) > \epsilon\} \subseteq M\]

Every sample that leads to algorithm failure must be a misleading sample. This insight allows us to bound the probability of failure by analyzing the probability of drawing a misleading sample.

1.4 Probabilistic Error Bounds

Now we can calculate the probability of drawing a misleading sample. First, we express \(M\) as a union:

\[M = \bigcup_{h \in \mathcal{H}_B} \{S|_x : L_S(h) = 0\}\]

This allows us to apply the union bound:

\[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_{(D,f)}(h_S) > \epsilon\}) \leq \mathcal{D}^m(M) \leq \sum_{h \in \mathcal{H}_B} \mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_S(h) = 0\})\]

Next, we calculate the probability that a specific bad hypothesis \(h\) has zero training error. Since the true error of \(h\) is greater than \(\epsilon\), and our samples are drawn independently:

\[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_S(h) = 0\}) = \mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : \forall i, h(x_i) = f(x_i)\}) = \prod_{i=1}^m \mathcal{D}(\{x_i : h(x_i) = f(x_i)\})\]

For each individual sample, the probability of correct classification is:

\[\mathcal{D}(\{x_i : h(x_i) = f(x_i)\}) = 1 - L_{(D,f)}(h) \leq 1 - \epsilon\]

Therefore: \[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_S(h) = 0\}) \leq (1 - \epsilon)^m\]

To simplify our expressions, we use the standard inequality \(1 - \epsilon \leq e^{-\epsilon}\), which gives us:

\[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_S(h) = 0\}) \leq (1 - \epsilon)^m \leq e^{-\epsilon m}\]

Combining this with our union bound:

\[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_{(D,f)}(h_S) > \epsilon\}) \leq \sum_{h \in \mathcal{H}_B} e^{-\epsilon m} = |\mathcal{H}_B| \cdot e^{-\epsilon m} \leq |\mathcal{H}| \cdot e^{-\epsilon m}\]

This gives us our fundamental bound: the probability of failure is at most \(|\mathcal{H}| \cdot e^{-\epsilon m}\).

1.5 The Probably Approximately Correct Framework

The bound we’ve derived forms the foundation of Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) learning. Let’s understand what it means in practical terms.

If we want to ensure that our algorithm fails with probability at most \(\delta\) (a confidence parameter), we need:

\[|\mathcal{H}| \cdot e^{-\epsilon m} \leq \delta\]

Solving for the required sample size \(m\):

\[e^{-\epsilon m} \leq \frac{\delta}{|\mathcal{H}|}\]

Taking logarithms:

\[-\epsilon m \leq \ln\left(\frac{\delta}{|\mathcal{H}|}\right) = \ln(\delta) - \ln(|\mathcal{H}|)\]

Dividing by \(-\epsilon\) and flipping the inequality:

\[m \geq \frac{\ln(|\mathcal{H}|) - \ln(\delta)}{\epsilon} = \frac{\ln(|\mathcal{H}|/\delta)}{\epsilon}\]

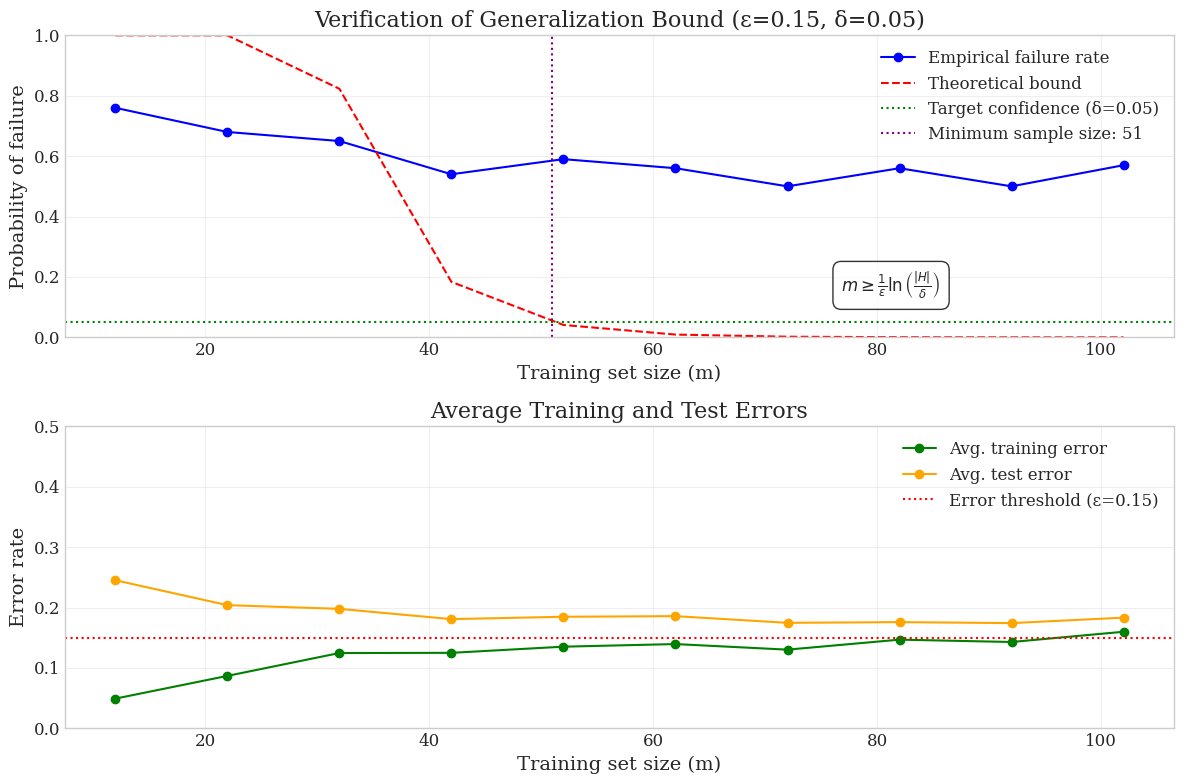

This gives us the PAC learning guarantee: With probability at least \(1-\delta\), a learning algorithm that outputs a hypothesis with zero training error will have true error at most \(\epsilon\), provided the training sample size is at least:

\[m \geq \frac{\ln(|\mathcal{H}|/\delta)}{\epsilon}\]

This is a fundamental result that tells us exactly how much data we need to learn effectively. It shows that the sample complexity: - Scales logarithmically with the size of the hypothesis class (\(|\mathcal{H}|\)) - Scales logarithmically with the inverse of the confidence parameter (\(1/\delta\)) - Scales linearly with the inverse of the error threshold (\(1/\epsilon\))

This means that we can learn even from very large hypothesis classes with a reasonable amount of data, as long as we’re willing to accept a small probability of failure and a small error threshold.

We can make the similar interpretation from the experiment shown in the image.

1.7 Summary and Looking Ahead

In this chapter, we developed the fundamental mathematics that allow us to provide guarantees about learning algorithms. Rather than relying on intuition or empirical evidence alone, we now have precise tools to analyze when and why learning succeeds.

Let’s review the key insights we’ve gained:

We formalized the learning problem through precise definitions of hypotheses, errors, and learning algorithms.

We identified that learning failure occurs when our algorithm outputs a hypothesis with high true error.

We discovered that such failure can only happen when our training sample is “misleading” - making a bad hypothesis look perfect.

We derived tight bounds on the probability of drawing misleading samples, leading to our fundamental inequality: \[\mathcal{D}^m(\{S|_x : L_{(D,f)}(h_S) > \epsilon\}) \leq |\mathcal{H}| \cdot e^{-\epsilon m}\]

We established the sample complexity of learning: \[m \geq \frac{\ln(|\mathcal{H}|/\delta)}{\epsilon}\] This tells us exactly how many examples we need to ensure our learning algorithm succeeds with high probability.

These results provide a solid mathematical foundation for understanding learning guarantees, but they rely on several assumptions that limit their direct application to many real-world scenarios. Most notably, we’ve worked under the realizability assumption (that a perfect hypothesis exists in our class), and we’ve assumed that our hypothesis class is finite.

In the next chapter, we’ll formalize and extend these insights by developing the Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) learning model. This model provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing learnability across different problem domains and algorithm types. We’ll remove the restrictive assumptions of this chapter, explore how to handle infinite hypothesis classes, and investigate learning without the realizability assumption.

By building on the mathematical foundations established here, we’ll develop a more complete understanding of what makes learning possible and what fundamental limitations exist in machine learning. This will ultimately help us answer one of the most profound questions in the field: What is learnable and what is not?